America’s Public Lands and Waters Threatened

Protection is the key to biodiversity, water quality and climate security.

“Izhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit”

In the Gwich’in language, that means “the sacred place where life begins.” The term refers to the coastal plain of Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) where some 200,000 Porcupine Caribou birth their young after making the longest land-based mammal migration on the planet. To witness this spectacle is an awe-inspiring experience within some of the greatest public lands on earth.

Along with multiple sails through the Arctic Ocean, I have visited the remote ANWR region along with other photographers and filmmakers from the International League of Conservation Photographers (ILCP). These efforts were to create awareness of the Arctic Refuge and highlight the threats of planned fossil-fuel development in the vast public lands of northern and Arctic Alaska.

GOP representatives have poked fun at the remote region for decades. They hold up white sheets of foam core to illustrate their public fairy tale that there is nothing there, so why not “Drill Baby Drill?” As part of the current “Big Beautiful Bill,” Sen. Mike Lee of Utah has added language to open vast wilderness for fossil fuel extraction and sell off other swaths of public lands to real estate moguls for “housing developments.”

We must fight and resist this land grab by Big Oil and greedy developers. This is our land. Below is a short story of the beautiful and vulnerable Arctic wilderness, and how the rapid changes there affect us locally far to the south. This vast region has been called the “American Serengeti,” full of migrating mammals and birds, untamed rivers, plentiful fish and unspoiled vistas.

At first sight, the grizzly bear seemed intoxicated. The feast of a freshly killed Porcupine Caribou had left the predator incapacitated and rolling around in the spongy tundra blocking our path up the valley between two mountains. We settled low with binoculars and observed the large male bear while caribou continued to pass behind. This was the wilderness experience I had hoped for and the Alaskan summer did not disappoint. We saw nearly two dozen grizzlies and thousands of caribou.

I have spent the last three decades sailing, and exploring, the ocean wilderness of the Arctic’s Northwest Passage. The sailing route takes one along the northern coast of Alaska in the icy Beaufort Sea. The continental shelf extends some 100 miles out to sea and these coastal waters are very shallow and dangerous as you approach the shoreline, especially with a deep draft sailboat. As I sailed by the Arctic Refuge twice, some 25 miles away, all I could think about was what I was missing if only we could stop and get our feet on the ground.

A decade later, I found myself 25 miles inland setting up basecamp with five fellow conservationists, 220 miles north of the Arctic Circle. We hiked daily outwards from our camp observing wildlife, all while documenting the vast, but fragile remote wilderness.

Besides the abundant wildlife, there are thousands of indigenous people, Gwich’in, living in 19 communities surrounding the refuge that depend on the caribou migration for sustainable hunting to provide food for their families. The tradition of balanced harvesting of animals has been taking place for multi-generations, whether it is Bowhead Whales from the Arctic Ocean or Porcupine Caribou from the Arctic Refuge.

The Gwich’in, also known as the “Caribou People,” have voiced grave concerns over pending fossil fuel development. Porcupine Caribou have predictably migrated through this region for millennia. This predictability is changing rapidly causing food insecurity and a potential cultural genocide. They are threatened by both climate disruption and potential fossil-fuel extraction affecting the sensitive coastal plain ecosystem.

There is no current development of any kind in the refuge. This could all change in the near future. The administration and Congress are attempting to open the coastal plain portion of the refuge to oil and gas development. The decision is highly controversial and has long-lasting ramifications.

The Arctic Report Card documents the rapid decline of caribou (or reindeer) populations worldwide. Fifty-six percent of all caribou, some 2.6 million animals, have died off in the past 20 years. Climate change in the Arctic has become a “threat multiplier.” Extreme seasonal changes have affected everything from bugs and parasites to winter snow cover. New freeze/thaw cycles combined with freezing rain are changing soft snow into icy barriers, making it impossible for caribou to forage.

The Arctic is warming twice as fast as any other region of the planet. Recent scientific studies have shown that it is imperative to protect public lands, forests and ocean ecosystems from development, especially the extraction of fossil-fuels, as they act as an important buffer system to absorb excess carbon and sequester it back in the ground. New oil and gas development in sensitive areas like the Arctic Refuge will harm not only wildlife and indigenous communities, but also threaten the earth’s carbon balance, potentially causing catastrophic climate change.

After my Arctic Refuge experience, I traveled back to “civilization” where I met with multiple polar and climate scientists from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. We discussed the rapidly changing Alaskan weather and climate patterns. I asked them all about how climate is affecting more southern states like Iowa. To a person, they all said instances of higher precipitation, sometimes catastrophic, were becoming more normal in the upper Midwest. They also mentioned rain on snow causing tremendous issues in the Arctic and this effect becoming more common in winter environments across the world.

Ironically, and unknown to me at the time, the day I met with the scientists, Northwest Iowa was experiencing a record, one-time rain event (7-10” in summer 2018) which caused a rapid rise in water levels flooding railroad tracks near the town of Doon. The flooding destabilized the tracks and derailed a train carrying tar sands oil causing a 200,000-gallon oil spill, the largest in state history. Much of the oil and debris was then trucked into the Dickinson County landfill and deposited in our watershed. This is the “threat multiplier” of climate change.

In March, with temperatures soaring to more than 20 degrees above average in the state of Alaska, we experienced a “bomb cyclone” event in the Midwest. This rain on snow event was the exact circumstance the climate scientists were talking to me about as a potential new risk factor of climate disruption. The effect was catastrophic flooding in both Iowa and Nebraska causing billions of dollars of damage by destroying infrastructure, communities and farmland.

What is happening in the Arctic is not staying in the Arctic. Normal weather patterns are being destabilized and we not immune. Iowa climate scientists have also been warning for decades of these coming changes.

Since we now constantly rebuild billions of dollars of infrastructure and farmland in the Upper Mississippi Watershed, the question looms, how do we implement a more “resilient” vision of the Midwestern landscape which helps slow down, contain and filter excess water? Do we rebuild based on 20th-Century weather patterns or factor in 21st-Century climate disruption? I believe the latter, and this connects us back to the Iowa Great Lakes, where I call home.

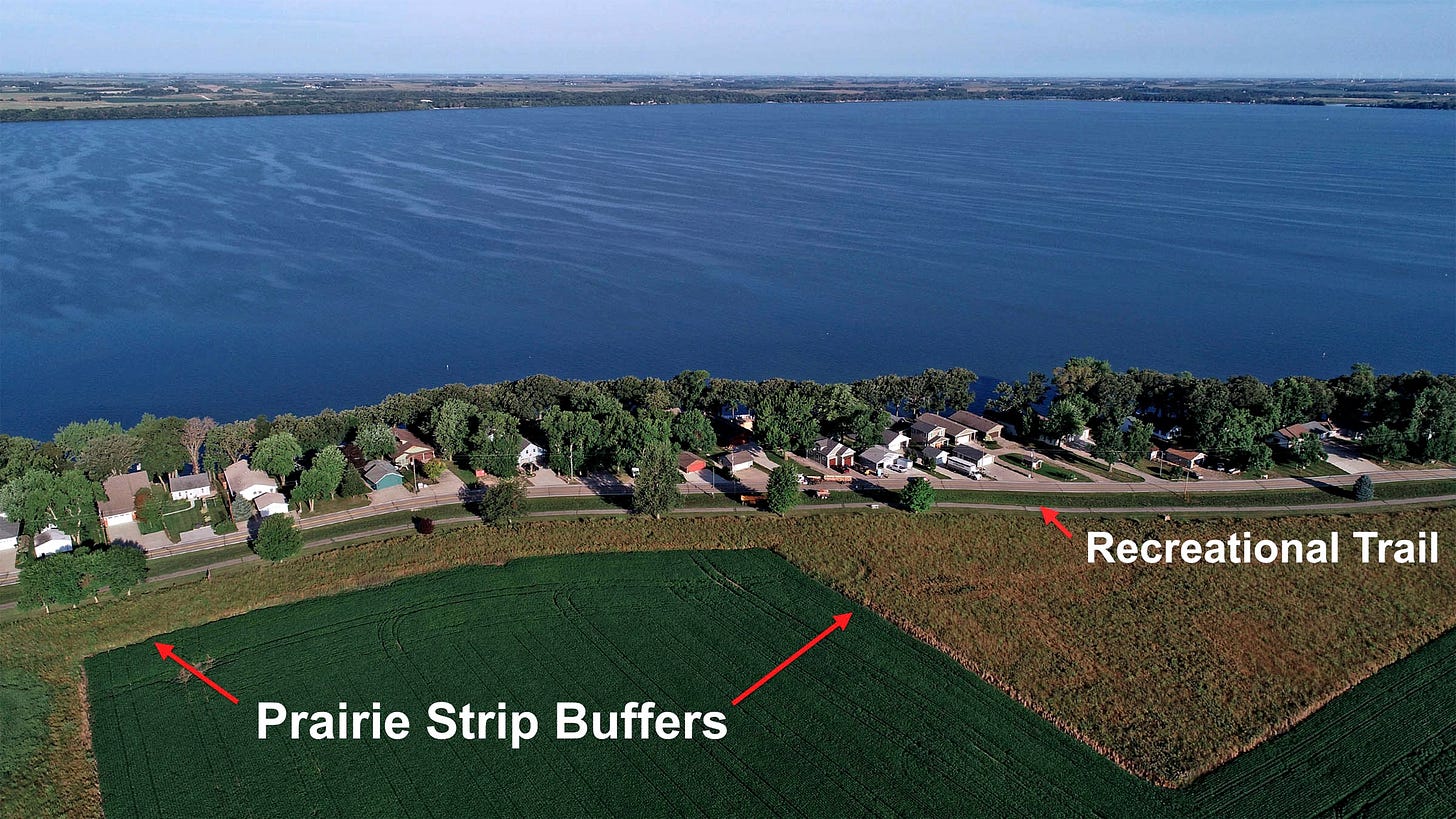

In Dickinson County, we have a more balanced economic model than the rest of the state of Iowa. We maintain high water quality standards, understand the importance of public lands, waters and healthy outdoor recreation. Our local economy is based on clean, public lands and waters. We buffer our important lakes by protecting and restoring natural features within our watershed.

A similar “rebalance” in favor of nature would benefit Iowa. We once had a vast wilderness of tallgrass prairie, wetlands and potholes (potential public lands and waters). This natural system slowed and filtered excess water before releasing it into rivers and lakes. By bringing a portion of this back in critical watersheds throughout the state we can create a new resilient landscape which solves our water crisis, addresses climate change, adds new recreation and energy corridors to the state.

The solutions to Iowa’s polluted water and climate crisis are within reach. The public supports conservation and climate action. We just need the leadership, vision and will to protect, and restore, our natural world while understanding the need for wilderness protection in critical regions of the globe. Think globally and act locally; because the rapid changes in the Arctic will not stay in the Arctic.

Call your senators and representatives. Tell them we need more public lands, not less.

Have you explored the variety of writers in the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative? We are writers and creators from around the state and contribute commentary and feature stories of interest to those who care about Iowa. Please consider a paid subscription.

I have wondered why Dickinson County has managed to have so much high quality public land. (I’ve also taught classes at Iowa Lakeside Lab…🙂). I’m guessing both county and state resources are involved. The “Iowa Great Lakes” are a special area, but as a central Iowan I would like to see the Dickinson County model widely adopted throughout the state.

Thanks for the personal perspective, David! We must HOPE that we've learned something about the need to protect lands and waters. Worldwide!